After living through the Great Recession of 2008, you might ask: “What is the best way to provide myself with retirement income that can sustain through future catastrophes?” This article answers this question, when considering extreme cases, including severe and prolonged declines, far worse than 2008.

Imagine that you are a retiree and are fully dependent on your investments to provide you with income for as long as you live. The amount can be your total estimated expenses minus any social security income and pension plans. You would like to receive a certain amount of income each year, with adjustments for inflation in subsequent years.

The ideal investment would survive all of the following:

- Withdrawals during a prolonged decline.

- Withdrawals growing with inflation, as well as hyperinflation.

- Withdrawals lasting for as long as you live.

- All local damages including natural disasters, theft, confiscation during a war, and legal changes.

- Change in supply and demand.

The risk of a short life: While longevity introduces the financial risk of running out of money, the risk of a short life is not a financial risk. By definition, if your money can support you for 30 years, it can support you for 29 years, 3 years or 3 days. Therefore, we limit the discussion of need #3: “Withdrawals lasting for as long as you live”, to the case of a long life. While this may sound trivial, some retirees confuse the health risk of a short life with a financial risk. To be clear – a short life, by definition, cannot be riskier than a long life, financially speaking.

When testing various investments, we can weed-out the ones that cannot survive any of the above:

- Cash, Checking, Savings, Money Market, High-Grade Bonds: These all have very low growth rates (#2, #3). Some even have negative real growth. Putting substantial portions of your money in any of these may help you temporarily during stock declines, but they all share longevity risk – running out of money. For a high enough allocation you are actually guaranteed to run out of money.

- Fixed annuities: A fixed annuity with inflation-adjusted income is exactly the product that should provide you with income for as long as you live. The problem is that it is backed by an insurance company. Bankruptcy of the company could hurt your annuity income. Given that your income depends on the solvency of a single company, the risk is too big to bear, no matter how stable the company seems. Additional problems are:

- Annuities with inflation protection tend to provide a very low payment.

- Nothing is left for your heirs, unless you accept an even lower payment.

- If you have a surprise expense at some point, there is no way to make a bigger withdrawal at one point, and make up for it later.

- Work: While not an investment, it is a way to provide retirement income. It is nice to work for as long as you enjoy it and are able to, but you cannot count on this for life. You may lose your job during an economic contraction (#1), or at any other time. Most people are not able to or do not want to work for as long as they live (#3).

- Tangible assets: Anything you can touch (tangible) is subject to local damages (#4). It can be stolen or lost, and therefore cannot be useful. The one exception is a limited amount of cash to keep you going, in case of no access to an ATM.

- Gold and other commodities: These do not generate any value (#3). Any change in real-price reflects changes in supply and demand (#5), making these speculative investments with zero expected real returns. In fact, after a 28% tax on long-term holding of gold (taxed as a collectible), storage costs and high transaction costs, you should expect negative real returns. None of these assets appreciate in value reliably during declines. Gold has been especially risky with a nearly 30-year decline to recovery period in recent history. Commodities tend to be highly volatile, and may decline in value irreversibly whenever replacements are found.

- Real Estate – Individual Properties: Any individual property is subject to local damages (#4). It can be destroyed in a natural disaster or war. Insurance may not cover all types of damages, and the insurance company may not stay solvent and able to repay all homeowners, in case of a large scale disaster. Even if all damages are covered, no rental income is available during the rebuilding of the property. Vacancies can occur also during economic downturns. Another risk is a drop in property values and rental income due to local changes, including irreparable structural problems, and change in demographics or job opportunities.

- Real Estate – Dispersed Individual Properties: Geographic dispersion can alleviate most of the problems described above, if the number of properties is large enough. To account for country-wide problems (including confiscation during wars), international dispersion is necessary. Structured correctly this may be a viable solution, but it is impractical for most individuals. If ownership is leveraged with mortgages, the risk of dropped income gets magnified. To own tens of properties with no leverage, you may need substantial resources, and still need an array of professionals to help with management, repairs and taxation. The result is not too appealing, because income after all expenses tends to be limited, and the growth of property values is not spectacular. In the very long run you can expect real estate to grow only in line with wage increases. In the past 100+ years, this was about 1% higher than inflation, providing minimal real growth.

- Real Estate – Pooled (REITs = Real Estate Investment Trusts): These investments are similar to stocks in terms of their volatility and returns. They can be held as a part of a diversified stock portfolio.

- Real Estate – Own Home: Owning your home has value beyond investment considerations. It can be a good idea, as long as you have large enough investments to supply you with ongoing income as well as money for maintaining your home.

- Stocks, concentrated portfolios: Concentrated stock portfolios may decline for many years, and may never recover.

- Stocks with a high withdrawal rate: Globally diversified portfolios have recovered from all declines, but with a high enough withdrawal rate, you may not live to enjoy the recovery period.

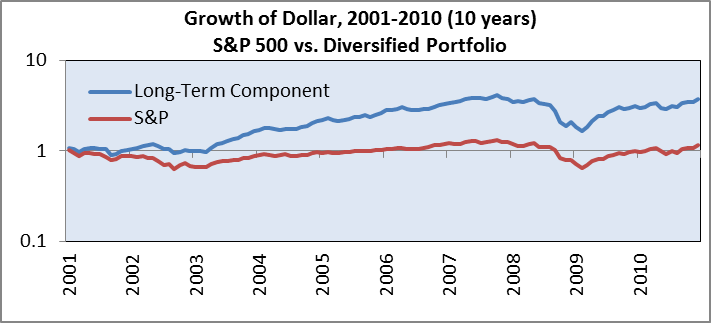

One investment that can survive all of the above: Globally diversified stocks with a low withdrawal rate, no market timing and representing entire markets . Below is a description of how it can survive the different risks:

- Withdrawals during a prolonged decline: Globally diversified portfolios have recovered from all declines, and it is reasonable to expect this trend to continue as long as people will want to get things in the cheapest and easiest way possible. With a low enough withdrawal rate, you can weather extreme declines.

- Withdrawals growing with inflation, even in the face of hyperinflation: Inflation represents the rise in cost of goods. By owning the companies that provide these goods, your investments grow with inflation over time.

- Withdrawals lasting for as long as you live: Given that company ownership provides the highest growth rate in the long run, diversified stocks provide the highest chance of lifelong income.

- All local damages including natural disasters, theft, confiscation during a war, and legal changes: Thanks to the global diversification, no local damage can decimate your entire portfolio.

- Change in supply and demand: A global stock portfolio holding companies in all industries, does not depend on demand for any specific product or service. If there is weaker demand for a specific product or service, this demand gets replaced by demand for an alternative that other companies in your portfolio provide. As long as people keep looking to get things done cheaply and simply, they will use the products and services of companies in your globally diversified portfolio.

Psychological Risks: Given the volatility of stocks, investing large portions of your money in them requires iron discipline. Many individuals lost substantial parts of their life’s savings during major market crashes due to fear. The best way to minimize this risk is to get the help of a professional that demonstrated iron discipline during stock declines, and kept his clients’ money as well as his/her own fully invested during those times.

Withdrawal Rate : The acceptable withdrawal rate from the stock portfolio depends on the portfolio. Some portfolios can withstand withdrawal rates of up to 4%, and survive substantial declines. To be prepared for very extreme and rare declines, that may occur less than once in a lifetime, you may want to go down as low as about 3%. The exact percentage depends on the portfolio.

Low Withdrawal Rate: If you can limit yourself to a very low withdraw rate from your globally diversified stock portfolio (with inflation adjustments), you may have the best plan for your retirement income, even at hypothetical times when people on the streets are begging for food.

With a very low withdrawal rate, putting a portion in more stable investments like cash or bonds will not help your already high short-term security (very low withdrawal rate), but will hurt your long-term security in the face of longevity and inflation.

Making up for a Higher Withdrawal Rate : For higher withdrawal rates, a limited allocation to bonds may provide you with income during severe declines and improve your security. Once you withdraw much more than 4%, there is nothing that can save you from extreme catastrophes.

What if this Solution is not Good Enough? You may feel that no matter how low you bring the withdrawal rate, there could always be a case that will result in a depletion of your assets. This is true, and it would be nice to get a perfect guarantee. Unfortunately, all alternatives fail under certain conditions. While no solution is perfect, the diversified stock solution is likely to withstand the most extreme scenarios.

When comparing the different risks, the odds for the global stock portfolio are much higher than the alternatives, thanks to the combination of high diversification and high average growth rate. Most other solutions fail in the face of inflation combined with longevity and/or concentration risks.

Summary

During substantial stock market declines, you may be concerned with the security of a diversified stock portfolio, and look for more stable alternatives. There are investments that suffer less extreme declines, but they suffer from other risks including inflation, longevity and various localized risks. When considering the entire bag of financial risks, diversified stocks provide the highest likelihood of success in providing lifelong retirement income. This is all subject to you or your advisor having iron discipline in staying invested at all times.

Disclosures Including Backtested Performance Data